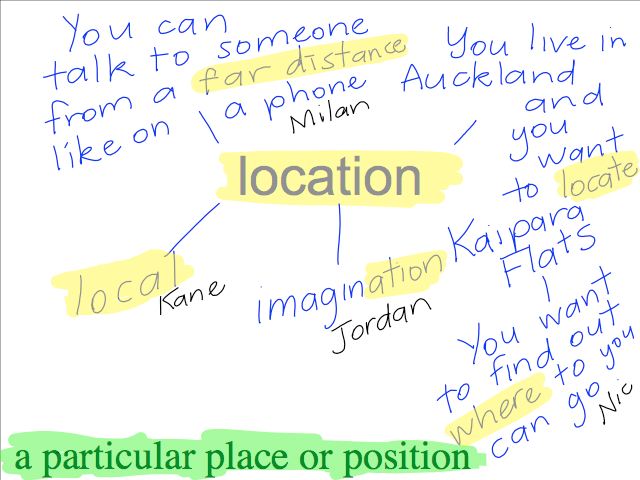

Locationary Definition

Perlocutionary act synonyms, Perlocutionary act pronunciation, Perlocutionary act translation, English dictionary definition of Perlocutionary act. N philosophy the effect that someone has by uttering certain words, such as frightening a person.

- In speech-act theory, a locutionary act is the act of making a meaningful utterance, a stretch of spoken language that is preceded by silence and followed by silence or a change of speaker —also known as a locution or an utterance act.

- January 15, 2021. 5 Tips for Becoming an Entrepreneur. January 4, 2021. Digital Tech Tips. Top 5 Analytics Software for the Business. September 25, 2019. Locationary is Business and Tech Blog.

Locutionary, Illocutionary and Perlocutioary Acts Between Modern linguistics and Traditional Arabic Linguistics

2011, Volume 35, Issue 55, Pages 1-25

Abstract

The present paper is part of a larger project to investigate the hypothesis that traditional Arab linguists were well acquainted with some of the main ideas and concepts of modern pragmatics. In this paper the researcher tries to find out whether Arab linguists were familiar with one of the major tenets of speech–act theory, namely, the analysis of a speech act (SA) into locutionary, illocutionary and perlocutionary acts, which J.L. Austin used in his analysis of speech acts. It is a commonplace assumption in the history of modern linguistics that speech-act theory and its key features were first proposed by Austin in the middle of the 20th century. The aim of this paper is to question that assumption; therefore, the problem or the question that the researcher undertakes to answer is whether Arab linguists of the past knew speech acts and were able to analyse them before modern linguists and philosophers like Austin , and consequently to see whether these aspects of the theory have a longer history than is assumed in the literature. The first part of the paper gives a survey of the above concepts as they appear in modern linguistic literature in the west . The second part deals with the Arabs' contribution to the same concepts and aspects of the theoryin an attempt to show their familiarity with them centuries before modern linguists. The method the researcher uses to achieve his aim is quoting from traditional books of Arab and Muslim linguists (rhetoricians and jurisprudents ) . Using samples of such quotations with special reference to directives , the researcher finds adequate evidence to support his hypothesis that Arab and Muslim linguists were familiar with the above concepts and analyses . The only difference is terminological and does not affect the findings in any significant way . The present paper is only a first step : It is recommended that future research should be carried out along the same lines to answer similar questions with even more adequate evidence .

Metrics

Related

You could argue Apple Maps’ lackluster debut last year had as much to do with our tendency to focus on sexy outlier goofs, as if those alone were sufficient evidence the app was problem-riddled. There’s no science behind that position, but the sensational resonates, and it’s eye-catching to learn that an industry darling like Apple might have crafted an app that embarrassingly confused, for instance, London, Ontario with London, England, or the lofty Willis (nee Sears) Tower in Chicago — the second tallest building in the U.S. — with a comparably stubby skyscraper dwarfed by its peers. Were those errors pathological? Who could say.

Even I succumbed to the “where there’s smoke there’s fire” mindset at first, switching to Google Maps via the iOS version of Chrome, then to Google’s standalone iOS Maps app released back in December to the tech-blog equivalent of trumpets, confetti and angels singing hosannas. When an app triggered Apple Maps, I killed it. I learned to work around Apple’s hooks, manually typing addresses into Google Maps instead of Safari, sacrificing the luxury of Apple’s seamless inline app connections for what I assumed was Google Maps’ greater fidelity.

But my experience over time has veered from popular sentiment. Google Maps was getting addresses wrong and dropping the GPS pin down on the road behind a business or on the wrong side of the street. In fact I started noticing the app was getting basic locations wrong roughly as often as Apple Maps does.

To be fair, neither Maps screws up most of the time: both take me from A to Z reliably, whether Z’s a business, a residence or some backwoods state park hangout. But whether Apple’s quiet refinements are paying dividends or we’ve been wrong about the app’s shortcomings (or Google Maps’ superiority) from the start — all I have is anecdotal evidence — I’ve slowly gravitated back to using Apple Maps as my primary locational tool.

So when I read that Apple had snatched up Canadian data startup Locationary, it struck me as less a reactionary maneuver to shore up deficiencies in a still-ailing application than a progressive, aggregative one designed to distinguish Apple Maps from the crowd.

The mapping software industry’s holy-holy isn’t cartographical fidelity (already on offer), it’s figuring out how to fold in detailed, accurate, and — most important of all — always up-to-date information about the locations you’re searching for (or near, or topically about). The future of maps, among other whiz-bang features like three-dimensional, real-time verisimilitude, is their becoming semantically sophisticated extensions of our inquiries, not — as Apple and Google Maps both currently work — the other way around, conjuring results, then handing us off to subordinates like Yelp and the like for evaluative drill-down.

Locationary, a portmanteau of location and dictionary, touts its “Saturn” platform as a way to synthesize and refine business profiles, taking component data from multiple sources (crowd-sourced, business-provided) and restructuring it as composite information — in other words, making sure business profiles are representative and up-to-date. The company describes its platform as using “a revolutionary real-time blending technology that can merge data from multiple sources as quickly as you can download it.” Think of it as another shot at a “neutral” connection hub, like LinkedIn for contact management, say, designed to unify disparate profile-building processes.

Mapping software is already complex enough without branching into far trickier services that intermingle locational and contextual information. We’re vectoring toward the sort of eerie moment you see in a movie like Minority Report, when Tom Cruise walks by those marketplace displays that react to him uniquely, hawking this or that service based on his profile in some aggregative system, but it’ll take a paradigm shift in profile administration to get us there.

The actual future is probably more private, of course: tiny screens that fit in our pockets and hands or that perch above our eyes, Google Glass-style. As Locationary CEO Grant Ritchie put it to The Globe and Mail a year ago: “In 10 years from now, our mobile phones are going to know everything being sold around us — what’s on sale and where, how much it costs, what’s available in stock and where.”

Reactionary Definition Government

But to get there, you have to do far better than manually phoning businesses to verify their information (as Ritchie claims Google’s been doing with Google Maps). If Locationary lives up to its claims then, and Apple’s at some point able to launch a version of Apple Maps that offers accurate, comprehensive, contextually meaningful locational information, it may indeed have something unprecedented to crow about.